Kaiser Permanente’s pioneering nurse-midwives

The 1970s nurse-midwife movement transformed delivery practices.

Carolyn Stadter, early Kaiser Permanente midwife, at Kaiser Permanente Vancouver Medical Center in 1989.

Expectant mothers deserve specialized care and support, especially during a pandemic. At Kaiser Permanente, that support often includes certified nurse-midwives who for decades have been part of our allied health team helping bring babies into the world, even in the most challenging of circumstances.

With the World Health Organization designating 2020 as the Year of the Nurse and Midwife, there is a new focus on how nurse-midwives can play a crucial role in women’s health care.

But the modern profession of medicine evolved with men in charge, marginalizing women’s roles at the beginning of the 20th century. By the 1960s, midwives — an almost exclusively female profession — worked mainly in low-income, remote rural areas or in large, inner-city hospitals to fill gaps left by shortages of physicians.

In the early 1970s, however, the nurse-midwife movement blossomed as second-wave feminism took hold and an increasing number of women demanded that childbirth be a less rigid and more natural process. Yet granting hospital privileges to nurse-midwives was generally opposed by primarily male obstetricians, who argued that nurse-midwives would only be needed in isolated communities where physicians were scarce.

In 1971, only 6 states allowed nurse-midwives to practice. That same year, Kaiser Permanente in Oregon took the bold move of hiring its first certified nurse-midwife. The obstetrics and gynecology department at the Bess Kaiser Hospital in Portland had been short-staffed, and department chief Harold Cohen, MD, hired Nancy Holmes, who had received her nursing degree and Master of Science in nursing, and certification in midwifery from Yale University.

Holmes was soon followed by Carolyn Stadter, who received similar professional training and academic degrees at Columbia University.

But Dr. Cohen was stymied by the state Board of Medical Examiners, which insisted on physician-only deliveries and demanded that these women register as physician assistants. Holmes quit rather than comply, and Stadter moved to nearby Vancouver, Washington, to continue practicing at a Kaiser Permanente clinic.

However, the die had been cast. In 1972, Jane Cassels Record, PhD, (senior economist at the Kaiser Foundation Health Services Research Center) and Dr. Cohen published "The Introduction of Midwifery in a Prepaid Group Practice” in the American Journal of Public Health. The authors described the challenging process of introducing a new category of care practitioner in the face of “open resistance” from some physicians. But, eventually, almost all of the doctors felt that the nurse-midwife program should be maintained and even expanded.

As the practice of using midwives became widespread, the new profession of certified nurse-midwife was added to the allied health team, which comprises professions distinct from dentistry, nursing, medicine, and pharmacy. Certified nurse-midwives are trained to care for women through a normal maternity cycle (prenatal, intranatal, and postnatal) and to assist in family planning.

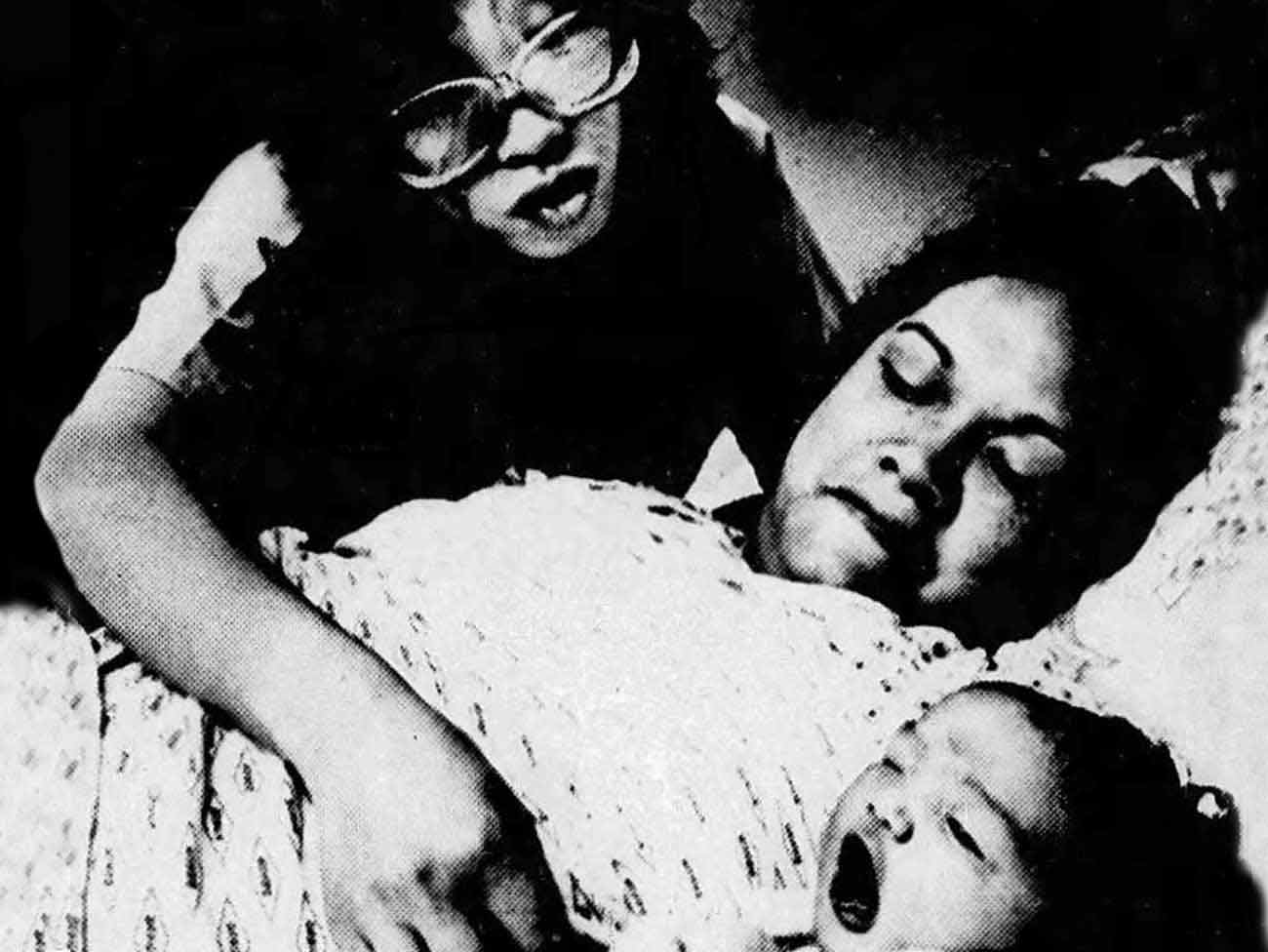

Nurse-midwife Marisa Chong, with Karen Morris and her newborn, at Orange County–Anaheim Medical Center on April 5, 1984.

In 1980, the Kaiser Permanente Orange County–Anaheim Medical Center in Southern California began a pilot program for certified nurse-midwives described by the Los Angeles Times as “the wave of the future,” and Marisa Chong and Janice Goings were the regional pioneers. As they moved into roles traditionally held by doctors, they had to prove themselves. And prove themselves they did; it wasn’t long before physicians were enthusiastic and supportive. By 1984, the program was so successful that 6 nurse-midwives were brought on staff, and by 1990 Kaiser Permanente medical centers in Northern California followed suit.

Many women, especially in low-risk delivery scenarios, prefer midwives for a range of reasons. Chong explained midwifery’s contribution to improving traditional obstetric practices: “If we consider childbearing a natural process but continue to treat the patient as though she is ill, we have failed to communicate its naturalness."

Institutional change, like childbirth, can be an intimidating process. But we all benefit when we challenge conventional assumptions and listen to trained professionals we trust. That’s culturally competent care. That’s what Kaiser Permanente did in 1971, and it’s what we continue to do today.